Circuit Breaker - Hope is not a Design Method

Context

Say you’re placing an order on a groceries app. You make the payment and you’re waiting for that happy payment confirmation screen with its melodious chime that almost always appears immediately. However, this time, it does not. You wait thirty long, painful seconds and are eventually annoyed to see a “Could not confirm payment” message.

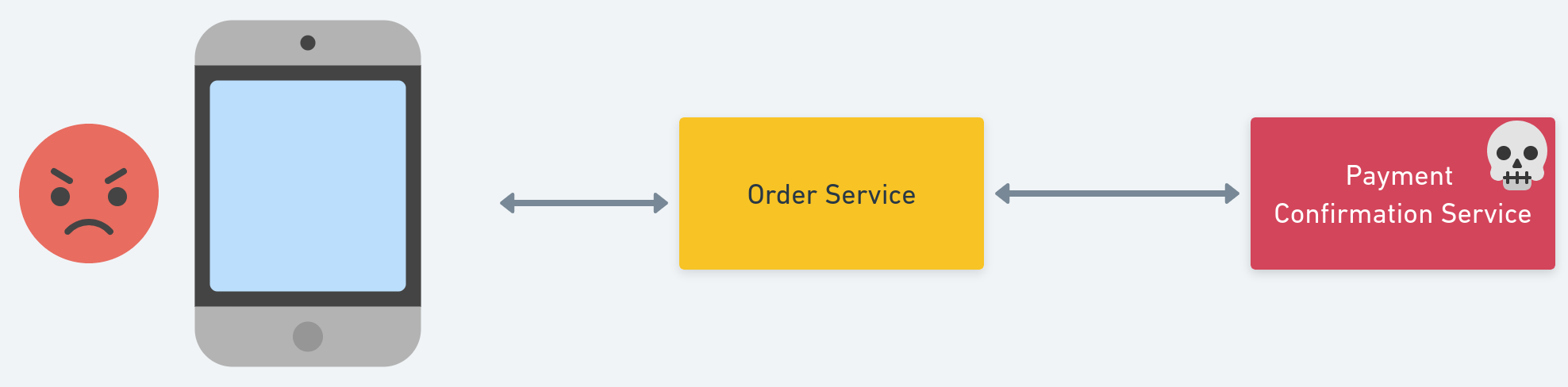

Now let’s say this is what normally happens when you make a payment: the app on your phone polls an order service hosted somewhere remote, which in turn polls a dedicated payment confirmation service.

Let’s say that the payment confirmation service is down due to some reason.

In a distributed system such as this, where there are multiple remote service calls to serve a transaction, failures can be broadly categorized into two types, based on their duration:

- Transient failures: these are resolved automatically after a short time interval (seconds). Reasons for these may include timeouts due to slow network connections, high load on the server, or any temporary issue. These can be handled by retrying the call.

- Failures that will take longer to fix: for example, the complete failure of a service or broken network connectivity. These are the type of failures that we’ll look at.

What Happens When a Dependency Fails

Let’s say we handle all failures of this frequently executed operation with a retry mechanism. The calling application (order service in the example above) will continually retry the remote call (a specified number of times). But we know that the retries will not succeed since the failure at the dependency (payment confirmation service in the above example) is not transient. What are the consequences?

- The transaction is blocked on this operation. It is using up resources - memory, threads, database connections and CPU cycles that are involved with this transaction. This is especially impactful to the overall performance of the calling application if the number of transactions that involve the dependency is high in volume or frequency - like grocery orders!

- Blocked transactions and holding resources wastefully will cause failures to cascade further to possibly unrelated parts of the system that might need to use the same resources. And this is not just at the calling service level where memory, threads, DB connections et cetera are being held. The service itself could be a resource to other remote components, which might also get affected since the calling service is not behaving as usual. In the grocery order payment example, resources on the user’s phone are being used by the app polling the order service.

- Continuous retries to the already failing dependency might put further load on it and perhaps prevent it from recovering

- And, in the example above, you have a lot of annoyed users that waited a long thirty seconds!

Great, Now What?

“Hope is not a design method."

~ Michael T. Nygard, Release It!: Design and Deploy Production-Ready Software

The key point to note here is that non-transient failures of a dependency shouldn’t be handled the same way as transient failures. We need a way of detecting that a failure is non-transient and acting accordingly. Another thing to note is that there’s nothing special about a remote service call here; any operation that is going to fail for a while can benefit from such a preventive arrangement. Let’s think through what we could do in such a scenario and lay down some requirements:

- Detect that the failing operation is probably going to keep failing for a while - it’s not a transient failure

- Fail fast - don’t waste resources attempting the operation; skip that operation and respond immediately with an appropriate exception when it’s known that it’s likely to fail for a while

- We need to eventually switch back to calling the operation. So, we need to detect if the problem has been fixed, and switch back when we are confident enough

Enter the Circuit Breaker

The circuit breaker pattern, popularized by Michael T. Nygard in his book, “Release It!", is what we can use in such a situation.

What it Does

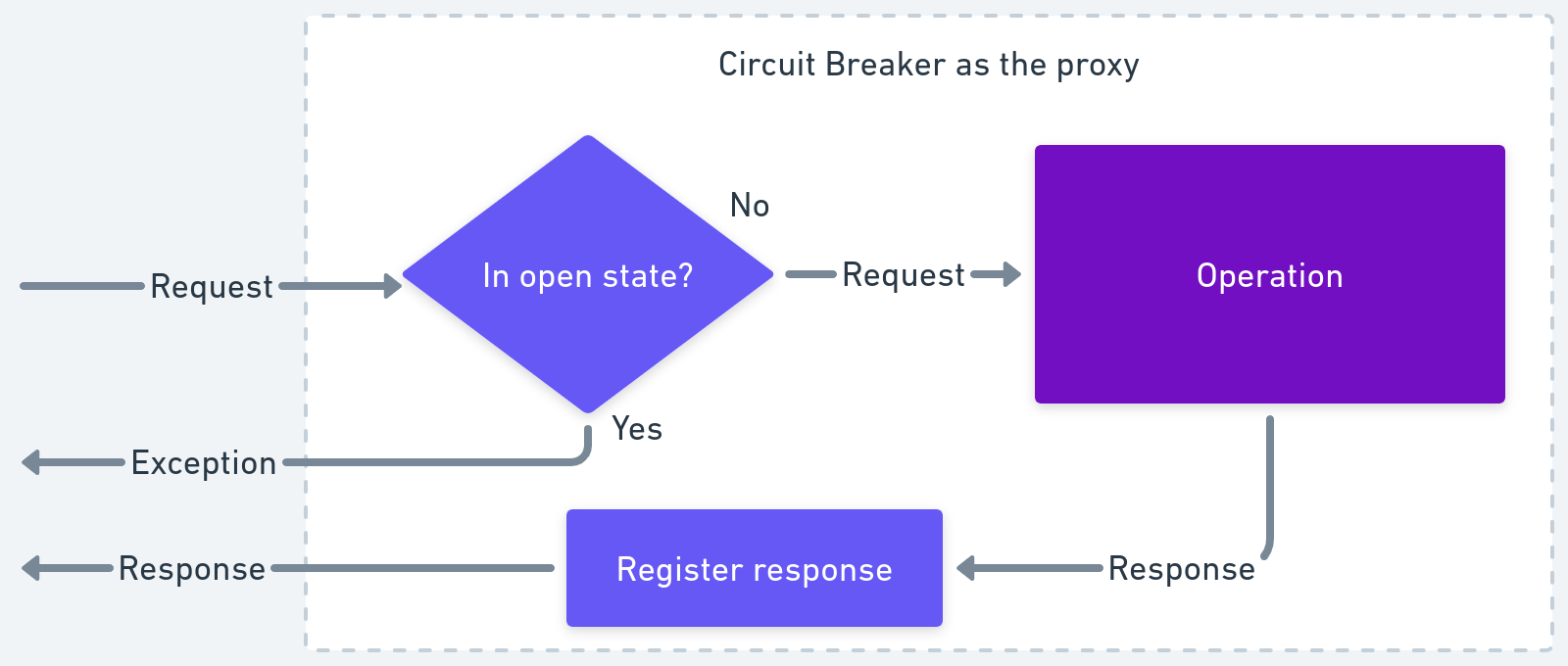

Simply said, a circuit breaker acts as a proxy for the operation that might fail. This proxy monitors the number of recent failures and decides whether to attempt the operation next time it is triggered or return an exception directly, skipping the operation. It tries the operation after some time and decides whether to switch back to invoking the operation normally that it is acting as a proxy for.

States of the Circuit Breaker

Overall, we can guess that the circuit breaker has three states. And the naming of these states is where the “circuit” analogy comes into play:

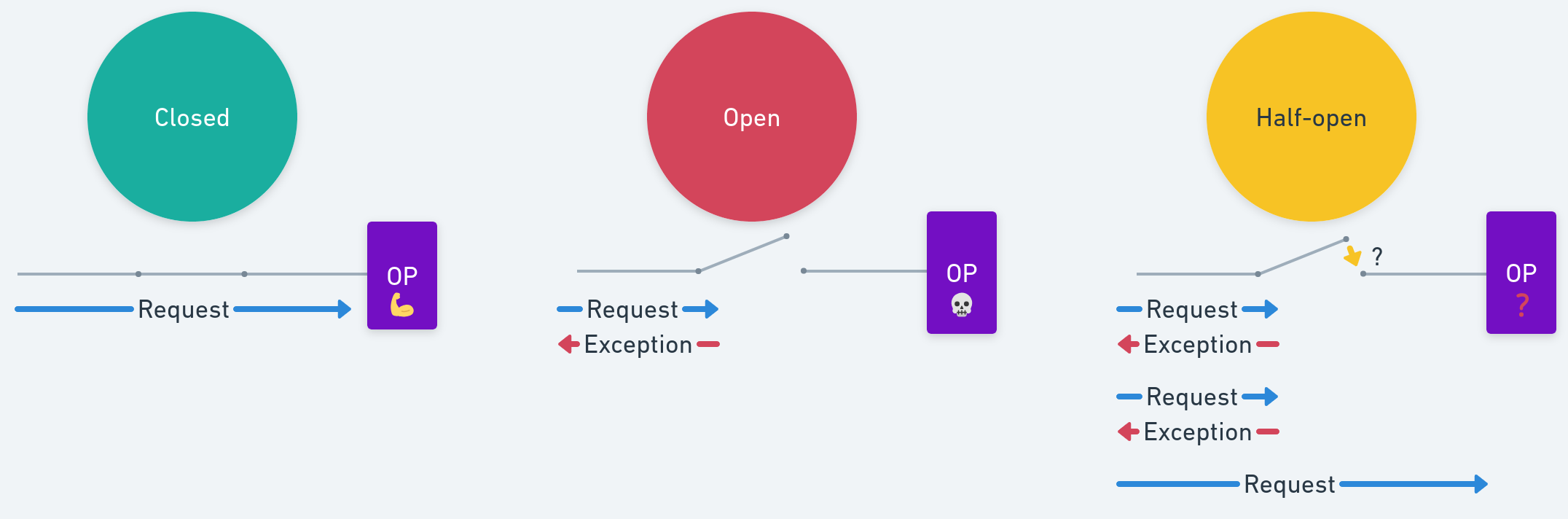

- Closed: The circuit is closed, so the request to the circuit breaker is routed to the operation which returns a response - the normal flow, so to speak. The operation can fail here, and the circuit breaker tracks these failures

- Open: The circuit is open, which means the request to the circuit breaker will not be routed to the operation. Instead, the circuit breaker will return an exception

- Half-open: This is the state in which the circuit breaker is ‘testing the water’; it allows a limited number of requests it receives to invoke the operation, to check whether the problem with the operation has been fixed

State transitions

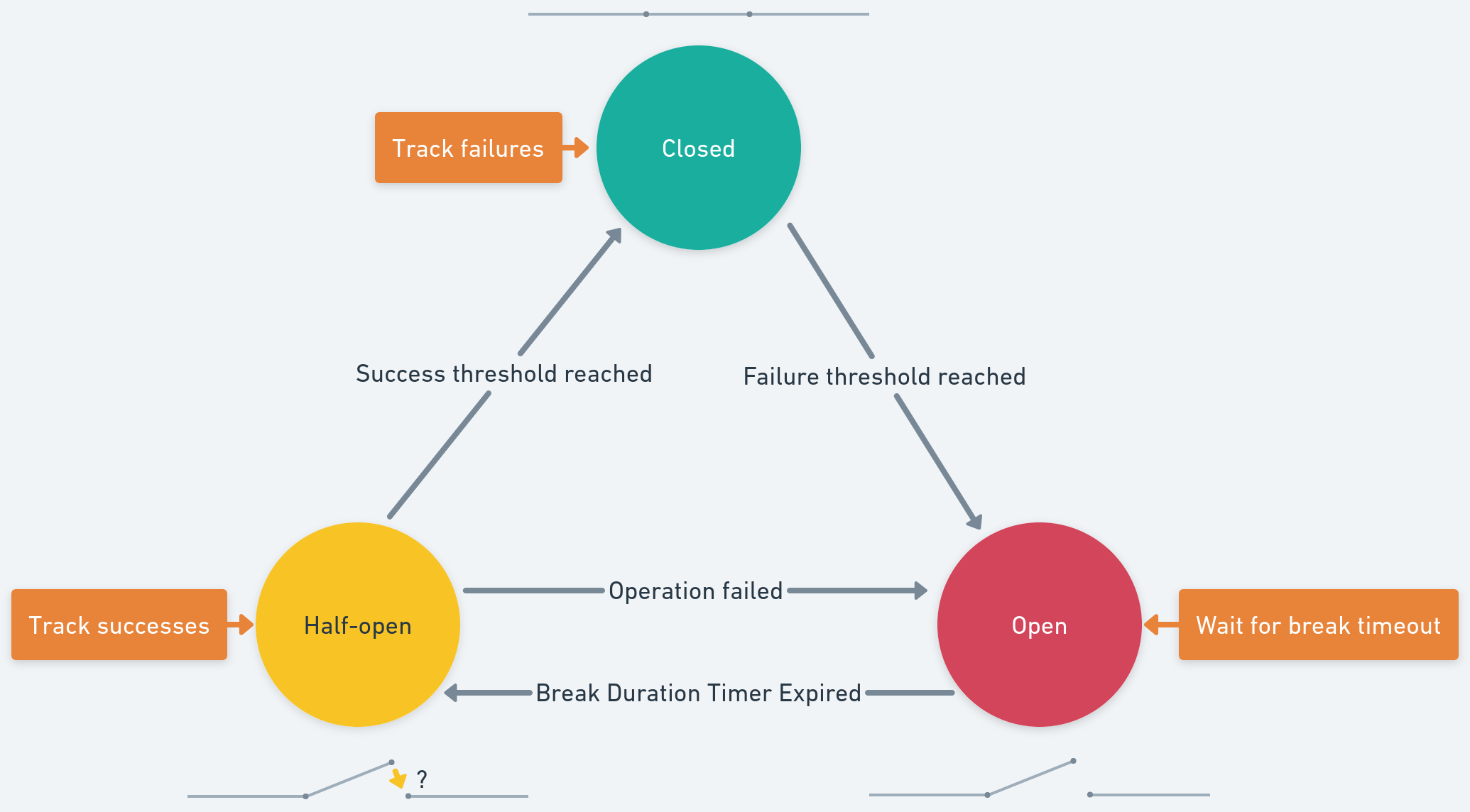

Let’s look at how the circuit breaker goes from one state to another:

- Closed $\rightarrow$ Open:

- While in the closed state, the circuit breaker maintains a count of the recent failures in invoking the operation

- If this count (with recency kept in consideration) exceeds the

failureThreshold, the circuit breaker transitions to the open state

- Open $\rightarrow$ Half-Open:

- While in the open state, a timer is set for

breakDuration - During this time, the operation is not invoked at all, and the circuit breaker responds with an exception. This is also the time during which the fault is expected to be fixed

- When the timer expires, the circuit breaker switches to the half-open state

- While in the open state, a timer is set for

- Half-Open $\rightarrow$ Open:

- Implementations can differ here, but here’s one of the simpler ones: the next requests to the circuit breaker when it’s in the half-open state are routed to the operation. If these invocations succeed, depending on the

successThreshold, the circuit breaker will eventually go to the closed state - However, if there is any failure before

successThresholdis reached, the circuit breaker reverts to the open state - Another implementation might allow a fraction of the incoming requests to invoke the operation to decide whether to switch to the closed state. This can be helpful, for example, if a remote service being called is recovering and we wouldn’t want to flood it immediately with the regular volume of requests.

- Implementations can differ here, but here’s one of the simpler ones: the next requests to the circuit breaker when it’s in the half-open state are routed to the operation. If these invocations succeed, depending on the

Usage

In code, the circuit breaker acts as a wrapper around the operation under consideration. So, any calls to the said operation go through the circuit breaker proxy.

Parameters

Different implementations require different parameters to be configured, but here are the core ones:

failureThreshold: The threshold (count or percentage) for failures after which the circuit breaks. Some advanced implementations also couple this with aminimumThroughput, so the failure threshold only takes effect when there’s a minimum amount of trafficbreakDuration: This specifies how long the circuit remains open before switching to the half-open state. Too low and there will be more failed invocations, while too high would mean a lot of failed transactions unless there’s a fallbacksuccessThreshold: The threshold (count or percentage) for successful invocations when in the half-open state for switching to the closed state

These values should be tuned by looking at existing traffic patterns and expected recovery time for non-transient failures. It’s difficult trying to estimate optimum values without this information.

Extras

Handling the Exception When the Circuit is Open

In the open state, the circuit breaker will return an exception. This exception can be handled according to the application. Here are some options:

- Report it appropriately to the user, asking them to try later. In the grocery app example, perhaps informing the user immediately that there was a problem in confirming their payment might be a little less annoying than making them wait for… thirty long seconds (okay, last time!)

- Try an alternative operation, like a fallback. Perhaps using a different way to confirm the payment, or users could be shown alternative payment options on their app

- Temporarily degrade the functionality of the system proactively instead of users getting an error at all, like making a payment method unavailable while the circuit is open

Break the Circuit Based on the Type of Exception

Most circuit breaker implementations allow the specification of the types of exceptions or results that should be considered when breaking a circuit. For example, exceptions arising from valid business logic conditions can be ignored by the circuit breaker while still tracking service unavailability exceptions. In the case of HTTP calls, perhaps some 4xx response codes (client error) could be ignored while 5xx codes could be tracked.

Log Circuit Events

Circuit breakers are a valuable place for monitoring. Any change in breaker state should be logged and breakers should reveal details of their state for deeper monitoring. Breaker behaviour is often a good source of warnings about deeper troubles in the environment.

~ Martin Fowler, in his blog about circuit breakers

As an example, the circuit breakers offered by Polly and resilience4j provide hooks into their state transitions, where you could log useful information. These logs could be tied to alerts for monitoring and observability.

Conclusion

Circuit breaker is a pattern to prevent an application from invoking an operation if it is highly likely to fail. This helps save resources, offer better response times and increase the stability of a system when it is in an error state or recovering from one. However, it’s not the best one to use in all cases. Using a circuit breaker isn’t recommended for handling access to local private resources in an application like in-memory data structures, since it will add a lot of overhead in this case. As mentioned above, retries are more suitable for transient failures. In fact, circuit breakers can be combined with retries to counter both types. It can also not be used as a substitute for handling business logic exceptions - it’s a fault tolerance and resilience pattern.